Energy transition for more climate protection

Target: climate neutral by 2035

Interview with Dr. rer. pol. Jens Clausen, Borderstep Institut

The Region Hannover and the state capital Hannover have made the commitment to be climate neutral by 2035. The aim is to reduce CO2 emissions and compensate for the remaining quantity of greenhouse gas. The target date 2035 is voluntary: the federal climate protection law states 2045 as deadline. But heat waves, storms and melting glaciers all over the world show that we are on the “Highway to Climate Hell”, to use the drastic words that UN Secretary General António Guterres used at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Egypt. The serious situation means a political obligation for the city and region. But where are we today? Are we already making successful progress on the way to becoming climate neutral?

The first indicator is the amount of energy consumed. This is measured in terawatt hours (TWh), a unit of measurement corresponding to a billion kilowatt hours. That is roughly the amount of energy needed each year to heat 50,000 detached houses. According to the “2020 energy and greenhouse gas balance sheet for the Region Hannover”, final energy consumption in the Region Hannover for 2022 amounted to around 25.2 TWh.

Supplying this amount of energy by sustainable means is a huge challenge. Jens Clausen sees it like that too. The graduate engineer has specialised in transformation research in the fields of energy and e-mobility. He works for the non-profit Borderstep Institute for Innovation and Sustainability that is funded by private and public-sector research work. The institute is based in Berlin, but Clausen, a co-founder of the institute, has been pursuing research in Hannover since 1991. He knows the situation in the region. We were able to talk to him.

The region’s energy requirements

Dr Clausen, according to the “2020 energy and greenhouse gas balance sheet for the Region Hannover”, around one third of the of final energy consumption amounting to 25 TWh is attributed to households, industry and transport. Where shall we begin?

Actually, I think it makes more sense to ask which sources of energy are actually being used! Firstly, we have 9 TWh natural gas, heating oil and coal that is being used for heating in industry, commerce, public facilities and households. Then we also have 7 TWh fuel, i.e. petrol and diesel, and 5 TWh electricity from the nationwide electricity mix that includes about 2 TWh from regenerative sources. But we are going to see certain shifts here.

Numerous heat pumps, the electrification of the transport sector and industrial process heat will need far more electricity than in the past. Currently, only 3 TWh fossil electricity needs to be replaced by green electricity. If we add the new requirements, the gap to be covered by green electricity is more likely to be 8 TWh.

Just a moment. Does this mean overall energy requirements would fall?

Yes, because you have to take the huge increase in efficiency into account. Using vehicles with electric motors rather than combustion engines boosts efficiency by a factor of 5. That saves about 4 TWh primary energy in the region. Replacing gas and oil central heating systems with heat pumps boosts efficiency by a factor of 3 and saves another 4 TWh. Refurbishment measures may save another 2 TWh. In other words: an electric car consumes less energy for the same distance at the same speed. The same applies accordingly to the heat pump. Altogether, future energy requirements are more likely to amount to 15 TWh rather than today’s 25 TWh, but with far more electricity being consumed than today.

Expanding wind power and photovoltaics

As a consequence, it will be a struggle for the region to cover the increasing demand for electricity. If we take a look at the essential steps that have to be taken to become climate neutral, what is the situation in terms of expanding wind power and photovoltaics?

The region is already searching intensively for possible wind turbine sites. The statutory amendments brought about on a national level in 2022 by Climate Action Minister Robert Habeck’s “Easter Package” have established new possibilities, at least with regard to the rotating radio beacons used by air traffic control. The new state government consisting of coalition of the SPD and The Greens also wants to improve conditions to facilitate the necessary marked increase in the number of wind turbines. At the end of August 2022, there were around 6,300 wind turbines in Lower Saxony, including about 250 in the region.

This number would have to be doubled or tripled to cover the demand for electricity.

But it’s not just about the quantity of wind turbines. Repowering a site with a larger new wind turbine will often generate far more electricity than an older, smaller system in the same place. In future, general acceptance in the population should be boosted by giving local authorities the possibility of sharing in the financial revenue earned when electricity is generated in their municipal territory. By the way, this applies to large free-standing photovoltaic arrays as well as wind turbines.

So what is the situation with generating solar electricity?

Clausen: The federal government has made PVs mandatory for all types of newbuild constructions. But that is not a great help because there are not so many newbuilds in progress. It is far more significant that the coalition agreement of the new state government intends to make PVs mandatory from 2025 whenever roofs are being renovated. Moreover, the state government is aiming at a target of around 250 km2 free-standing photovoltaic arrays, which would mean about 10 km2 PV arrays for the Region Hannover. But that would probably still not be enough.

PV arrays on 3x3 three kilometres of land, together with lots of new wind turbines: that doesn’t really look very nice. Would it not make more sense to put PV panels on existing roofs and car parks throughout the region by setting economic incentives or imposing a corresponding obligation?

The region probably has energy crops growing on around 160 km2 of land. That is intensive farming without much biodiversity. That doesn’t look very nice either. On the other hand, flowering plants and insects can flourish under free-standing PV arrays. We just have to learn to deal with things differently. And we must not forget that we want a lot of building to be done quickly. Progress can be made much faster in open spaces than if every 10 m2 has to be planned separately. Another major task consists in getting the systems installed at all in the face of the supply chain problems and the skills shortage. None of this is easy. At least it can be said that the region’s efforts to be climate neutral by 2035 are now receiving state and federal support. But the regional administration should never forget how high the target is, given the additional 8 TWh green electricity that will be needed by 2035. Although some of this can be produced outside the region, a lot will still have to be generated here.

Heating transition in households, industry and commerce

Let’s look at the heating transition in households. What is the situation here?

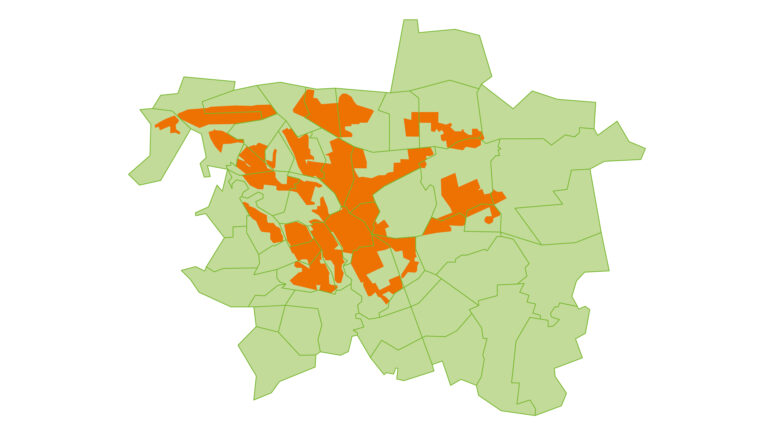

Clausen: We expect the federal and state authorities to make heating planning mandatory, with obligations to be met particularly by the local authorities and thus also the Region Hannover. Hannover has adopted a municipal heating plan for 2022. It provides the framework for transforming the heating supply in households and commerce, retail and the services. District and local heating networks are to be constructed or extended in densely built-up residential areas.

The smaller towns are staying out of this at the moment. But surely places such as Barsinghausen, Burgdorf and Wunstorf must also have corresponding potential, particularly in combination with biomass.

That is not correct. The town of Springe has installed a heating network but unfortunately it is headed by biomass. Other countries are cutting down primeval forests to supply Germany with wood for heating. Wood and biomass in general are scarce resources, and the science community is warning that climate change will make them even more scarce in future. Preference should be given to other solutions for new heating networks. Wunstorf is considering whether to use heat from the old Sigmundshall mine for a new heating network.

But Hannover is certainly the region’s district heating pioneer with the district heating bylaw adopted in 2022. As a result, from 2023 onwards enercity will be connecting more and more buildings to the district heating network, increasing the number from currently 3,500 at present to possibly more than 10,000 in 2035. Heating control systems will also be digitalised when buildings are connected up to the district heating network. This boosts efficiency with further considerable savings and makes another contribution toward becoming climate neutral. The district heating must of course be produced by regenerative methods. Besides incinerating waste, sewage sludge and waste wood, other possible heat sources being discussed include waste heat from industry, geothermal energy and heat pumps. The city utility company wants to generate 50% of its district heating from renewable energy sources by 2025, and increase this to 75 % by 2027.

Outside the district heating priority areas, will heat pumps dominate in future?

Yes. We and many others presume that the federal government will prohibit the installation of conventional oil and gas central heating systems from January 2024, apart from few exceptions. As a result, we are currently seeing a clear increase in the demand for heat pumps, al_though Climate Action Minister Habeck has changed the KfW funding. Less funding is now available in many cases, but more in others. There is certainly great interest in heat pumps. During the “Week of the Heat Pump” that I coordinated in October 2022, 2,500 people came to find out about the possibilities of this heating technology.

All that remains is to ask how private citizens and small businesses are supposed to pay for the changeover. There has evidently been a clear increase in the costs for heat pump systems. Then there are the costs for the electricity they need. Is this really economical?

The times of cheap gas, which we use for heating at the expense of our children and grandchildren, are probably finally over. But while many of us think it’s quite normal to pay 40,000 Euro for a car, we shake our heads at paying similar amounts for a central heating system. Does speed matter more than warmth? Nor do people ask if it’s economical to buy a new television. In future, central heating systems probably won’t be economical in the sense of being cheaper than they used to be. But they will be worth it, because otherwise we just won’t get the heat we need.

But what’s the situation with the housing stock? These buildings are usually poorly insulated, which prevents the use of heat pumps.

You can’t really generalise like that. In fact, countless examples prove exactly the opposite so we’ll see an increase in the number of heat pumps in existing buildings. More and more house owners advocate consistent electrification. This kind of system consists of a photovoltaic array preferably with more than 10 kW peak power, electricity storage, a heat pump and a charge station for their electric car. The first examples in the region show that a fairly well insulated detached house can thus become extensively self-sufficient in terms of its energy needs. Furthermore, the energy costs for electricity, heating and driving decrease to a few hundred Euro each year. It can be expected that with this goal in mind, many people who own a detached house will become actively involved in the energy transition.

What about hydrogen and biomass? Biomass in particular could be interesting: energy collected in the region from organic waste bins and from the fields and woods that reliably provides heat and electricity regardless of wind and sun.

Hydrogen will be relevant, but it will be too late for our goal of 2035. According to the current political consensus, it will never flow in Hannover’s natural gas distribution network: the intention is to reduce the natural gas network in the course of expanding the district heating system.

As far as biomass is concerned: as already mentioned, this is a scarce resource and will become even more so as a consequence of climate change. The federal government is already warning against it. Particularly the production of wood as fuel is not necessarily sustainable, and many harmful substances are emitted when it burns.

Do you agree that the real problems of the energy transition consist of the climate-neutral provision of process heat for industry?

Yes. It is not only the high electricity costs that stand in the way of electrifying the process heat supply in Germany. Up to now, not enough thought has been given to planning the expansion of the electricity network to supply additional major consumers. Indeed, the planning process has not even begun. For example, there are two cement plants in the Region Hannover that emit altogether about one million tonnes CO2 every year. The operators are trying to make progress, but up to now, not even the waste heat from the plant facilities is fed into the district heating network.

The traffic transition

Traffic transition is a dazzling but also controversial expression. Some don’t want to change car traffic at all and think electrification will do the job. Some want to reduce car traffic volumes, while others want to cut back on the stock of cars. What do you think?

There are too many cars out there. Many are much too big and their huge weight means they consume resources when in use, let alone the resources consumed when manufacturing the vehicles. And then there’s the high consumption of fuel. Cars with combustion engines are highly inefficient because they lose three quarters of the energy out of the exhaust pipe as heat. But a consistent traffic transition is hard work for politicians, because it interferes with peoples’ daily routines. The way cars are used is also a result of 70 years of modifying the region’s towns and villages to make them car-friendly. The places where we live, work, learn and shop are often so far apart that having a car seems to be the only way to cope. But here there’s something that we as consumers can do. For example, we can cycle or walk the many short distances that we still use the car for.

It’s a case of safeguarding mobility while reducing individual traffic. One way of doing this is to focus on traffic-reducing urban development by making it less appealing to use the car. Reducing the number of car parks and making them more expensive car parks would help, together with and a consistent speed limit of 30 kmh all over town would help. To become consistently climate neutral by 2035, all cars with a combustion engine must disappear from the roads, or be re_placed by electric cars.

The charging infrastructure is already being expanded in the region. But more incentives are needed to stimulate the demand for electric cars, for example, by announcing that all fuel stations selling fossil petrol and diesel will be closed by 2035. Fossil fuels are not compatible with being climate neutral.

Is it enough just to make it less attractive to drive cars? Do we not also need better cycle paths and improved local public transport?

Yes of course. We need a dense network of cycling routes and bike expressways. Bus and train services must be expanded. Above all, we need new flexible services such as “Moia” or “Sprinti”, which is currently just operating in a few towns on the outskirts of Hannover. These are basically taxi-sharing concepts without fixed routes and stops, bringing people from A to B at any time and at really low prices.

But the results of the traffic transition hitherto are rather poor, to put it mildly. According to the Region Hannover, in 2011, cars, i.e. drivers and passengers, accounted for a 49 % share of the traffic volume according to the Region Hannover. This figure was still 45 % in 2020. In the same period, the share of local public transport fell from 15 to 14 %. Bicycle traffic increased from 15 to 17 %.

Even role-model cities like Copenhagen show that it takes a long time to get people out of the car and onto the bike or bus. Here too, I think that efficient electric cars that use more than 80% of their energy for propulsion will play an important role for many people in the years to come. But please, not as three-tonne high-speed cars with gigantic batteries that tie up large amounts of resources.

All in all, we are facing huge tasks.

On the other hand, political actors on all levels in the cities, regions, state and federal government are tackling these tasks, not least as a result of new political coalitions. They must continue to expect strong headwinds in future too, and it will be difficult to persevere in asserting the measures consistently against all resistance. What we need is positive future scenarios, such as the electrified home with extremely low energy costs, or a vision of future mobility that is attractive precisely because it manages with few cars. In the end, we also have to think of tenants in high-rise buildings. We must not forget them when it comes to the self-sufficiency advantages of solar electricity. But this is primarily the obligation of the federal government.

Header picture: Tarnero/stockAdobe.com